January 05, 2026

The Market & The Mission: Why US Leadership in Multi-Domain Autonomy Depends on a Unified Regulatory Framework

Introduction

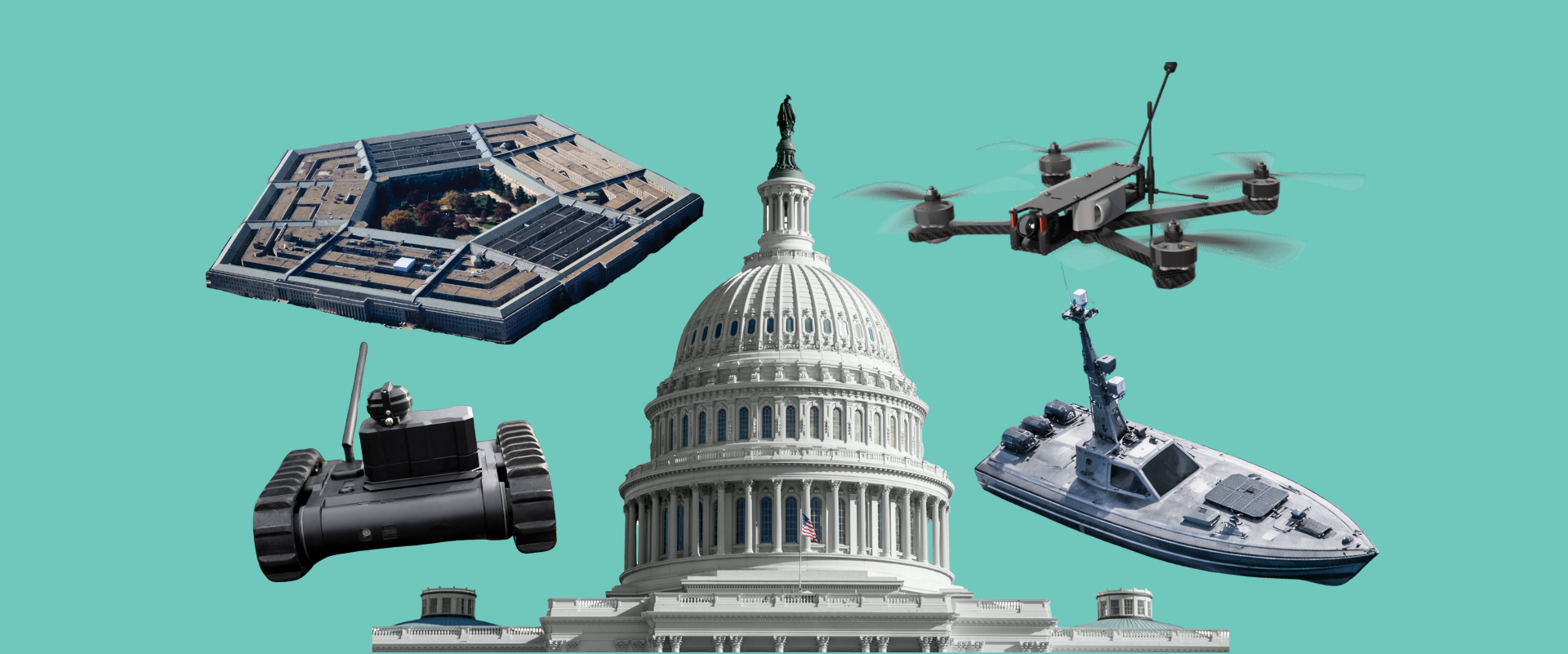

Not long ago, “unmanned systems” referred to drones – remotely piloted unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) operating in airspace under strict Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) rules. But as innovation has accelerated over the past decade, fully autonomous capabilities have become more sophisticated, affordable, and prevalent, enabling systems to make decisions and act without human intervention. And today, that autonomy is no longer confined to the skies.

Unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) now survey oceans, unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) patrol pipelines, and subsurface vehicles (UUVs) map the seafloor – multi-domain autonomy is here, faster than many anticipated. The problem is that regulation has not kept pace.

The United States now faces a choice: continue regulating autonomous systems through fragmented, domain-specific regimes, or modernize oversight to reflect how autonomy is actually being built, deployed, and scaled. This decision has direct consequences for national security, economic competitiveness, supply-chain resilience, and America’s ability to set global standards rather than inherit them.

A Patchwork of Silos

Instead of an integrated regulatory approach, the US is operating under a mishmash of siloed, domain-specific frameworks. Air autonomy is governed by the FAA, sea autonomy falls under Coast Guard purview, and land autonomy is fragmented across Department of Defense (DoD) programs, state laws, and municipal ordinances. Each governing body works in isolation, producing redundancy and delays that slow innovation and weaken our country’s competitiveness.

This fragmentation is not a result of agency failure, but of statutory design. Regulators are executing within authorities written for earlier manned technologies. Without congressional direction or executive coordination mechanisms, no single agency has the mandate or incentive to harmonize standards across domains. As a result, innovation that spans air, land, and sea is forced through regulatory structures that were never meant to interoperate.

There is a precedent for doing better. When the DoD invested in developing GPS in the 1970s-1980s, it was intended as a military navigation system. What made it transformative was a unified standard that allowed the same system to power universal navigation for everything from air navigation and global shipping to ride-sharing. Autonomy requires a similar policy decision today: a unified, risk-based regulatory framework that allows innovation to scale across domains. Without it, the US risks ceding leadership in a technology that is shaping both the battlefield and the economy.

The Asymmetry Problem

Autonomy is one ecosystem, but certification is splintered. In the air, the FAA manages UAS through Part 107 (small drones), Part 108 (Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations), Part 91 (large drones), and endless waivers, exemptions, and authorizations for advanced capabilities. Progress is slow, creating a “waiver culture” where innovators must beg for exemptions just to test BVLOS, swarms, or operations in congested areas, and over people. At sea, the Coast Guard regulates safety and navigation, but unmanned vessels still fall into gray zones. Companies testing USVs often face ambiguity about which rules apply, particularly when operating in commercial shipping lanes or when countering spoofing. And on land, the problem is fragmentation. DoD programs run separate certification processes inside acquisition silos. States and cities pile on their own laws, so a robot cleared to operate in one jurisdiction may be banned in the next. In this confusion, innovators end up fighting three battles at once, even when developing a single autonomy stack. That redundancy raises costs, slows time to market, and fragments an industry that is inherently converging.

Strategic competitors do not face the same constraints. Countries with centralized regulatory authority can field integrated air-sea-land autonomous systems more quickly, iterate operational concepts faster, and align industrial policy directly with deployment. In contrast, US firms must navigate three separate certification pathways for what is often the same underlying autonomy software—slowing adoption and weakening deterrence at precisely the moment speed matters most.

What Happens When Regulations Don’t Keep Up

Capabilities are moving faster than rules. In the past, a 15-minute drone flight was considered noteworthy. Today, small fixed-wing UAS can remain airborne for 6-8 hours, using AI-enabled vision to monitor crops, inspect infrastructure, or track moving targets. USVs are conducting months-long maritime missions with minimal human oversight, and ground robots are already making deliveries in urban areas. Yet, certification processes remain sluggish, parochial, and disconnected.

Treating each domain in isolation creates bottlenecks that make scaling nearly impossible. For example, a logistics firm trying to integrate drones, USVs, and UGVs into one supply chain would face three distinct regulatory gauntlets, each with different terminology, risk models, and compliance cycles. That’s the wrong model. Autonomy should exist on a continuum of regulation, much like aviation evolved over time. Ultralights, helicopters, and jets coexist under a unified framework with shared definitions, but harmonized in structure. Autonomy demands similar consideration.

Why We Need a Unified Framework

The case for a unified, risk-based framework is both practical and strategic. As technology advances, autonomy becomes more modular, allowing core components to be adapted across various vehicles. For example, software trained to identify obstacles on land can now be modified to support sea navigation. Interoperability strengthens the case. Just as communication networks rely on standard protocols like TCP/IP and smartphones rely on standardized APIs, autonomy requires a common certification framework. Shared test ranges, traffic management systems, and operator definitions would all lower costs and expand adoption.

In regulatory circles, unification is not a novel concept. International commerce presents similar issues to multidomain operations: An operator may operate across hundreds of nations, each with their own regulatory frameworks. Organizations such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) form international compacts to standardize aviation regulations globally. We should explore a similar framework: Design consensus standards and establish reciprocity agreements across domain-specific regulators, rather than nation-states.

For this to happen, some key harmonization is required:

- Operator Definition. Regulatory frameworks should define operator qualifications and responsibilities consistently across domains. Whether managing drones, USVs, or UGVs, organizations deploying autonomous systems should be held to equivalent safety, oversight, and accountability standards when the underlying autonomy stack is functionally the same.

- Traffic Coordination. Air corridors, maritime routes, and ground rights-of-way must interconnect so systems can hand off safely. We can do it with seaplanes. Why not drones?

- Testing & Certification. Shared test ranges that validate autonomy performance, counter-spoofing, and fail-safe mechanisms across domains would dramatically reduce cost. Certification must measure capability and risk, not just legacy vehicle types.

- Trusted Sourcing. Supply chain rules should extend across domains. A vetted autopilot shouldn’t need recertification every time it’s adapted to a new platform.

This unified framework would enable autonomy to scale like software, allowing companies to move towards a kind of “app store” model of autonomy: different vehicles, but a common interface and certification logic.

Without convergence, the US faces multiple risks. First, the American drone ecosystem faces a lot of headwinds and is being backstopped by shifting industrial policy. Innovators iterate in months, but regulators often take years, forcing companies to stick to narrow applications. Second, strategic disadvantage. Rivals like China aren’t shackled by fragmented oversight. They’re already demonstrating swarm operations and integrated air-sea missions. Delay here means reduced deterrence and lost competitiveness. And third, inefficiency. Maintaining three overlapping certification regimes is wasteful and unnecessary to maintain a reasonable standard of safety; standardization cuts costs and clarifies expectations. Action here is critical because if agencies diverge too far now, reconvergence later may be impossible.

Barriers to Convergence

If the logic for convergence is clear, why hasn’t it happened yet? The answer lies in institutional, cultural, and legal inertia. Agencies like the FAA, USCG, and DHS operate under distinct mandates, each with its own risk tolerance and bureaucratic culture. Sharing jurisdiction inevitably raises turf battles, and no agency wants to give up oversight authority.

There’s also the seemingly benign (but important) issue of nomenclature, since legacy legal definitions for terms like “navigable airspace” and “navigable waters” were designed for manned vehicles, not autonomous ones. Procurement models compound the problem further, because defense acquisition still assumes long lifecycles and fixed specifications, while autonomy requires rapid prototyping and software-driven updates. This sort of regulatory uncertainty makes it harder for acquisition officers to take risks on new systems.

Charting a New Course: 4 Steps Forward

A way through this regulatory quagmire is possible. The following four policy actions would meaningfully accelerate deployment while maintaining safety and accountability:

- Establish a Cross-Agency Autonomy Council. This body would standardize definitions, risk categories, test protocols, and certification processes across FAA, USCG, DoD, and DHS.

- Create Multi-Domain Test Ranges. Shared ranges would allow air, sea, and land systems to be tested together, validating not just autonomy performance but also interoperability and counter-autonomy resilience.

- Mandate Interoperability Standards. Just as NATO standardization agreements (or STANAGs) drive interoperability across allied systems, the US should codify standards for autonomy architectures, including APIs, communications protocols, and C2 systems that work across platforms.

- Move Beyond Waiver Culture. BVLOS operations, counter-autonomy measures, and operator qualifications should be codified in rulemaking, not left to piecemeal exemptions, and a clear rulebook would create certainty and drive investment.

A Unified Regulatory Framework for the Future

The US cannot certify 21st-century technologies with 20th-century frameworks. By establishing a unified regulatory model, we would reduce costs by scaling certification, drive affordability at scale, and preserve US leadership in autonomy across defense and commercial sectors. Our country has an opportunity to set a new global standard – if we act decisively, now.

For a PDF version of the report, click here.