June 25, 2024

FUZZY LOGIC: A Novel “Innovation Archetype Matrix” To Guide Government, Corporate, and Nonprofit Innovation Efforts

TL;DR

- Time pressure, existing materials, overarching goals, and the level of theoretical or empirical knowledge all impact innovation.

- This piece introduces a novel framework to describe the particular properties of four distinct archetypes of innovation: Goal-Driven Innovation, Utility-Driven Innovation, Crisis-Driven Innovation, and Process-Driven Innovation.

- Challenge competition owners, technologists, and others can use this framework for additional clarity and specificity when designing new calls for innovation.

Here, I present a new functional framework for innovation that aims to describe four “archetypes” of innovation and advise top-down government, industry, and NGO initiatives on how to best optimize the properties of each innovation archetype. The framework provides the names and particular properties of each archetype in the hope that this will lead to a heightened level of clarity and specificity when designing new calls for innovation.

Innovation Archetypes

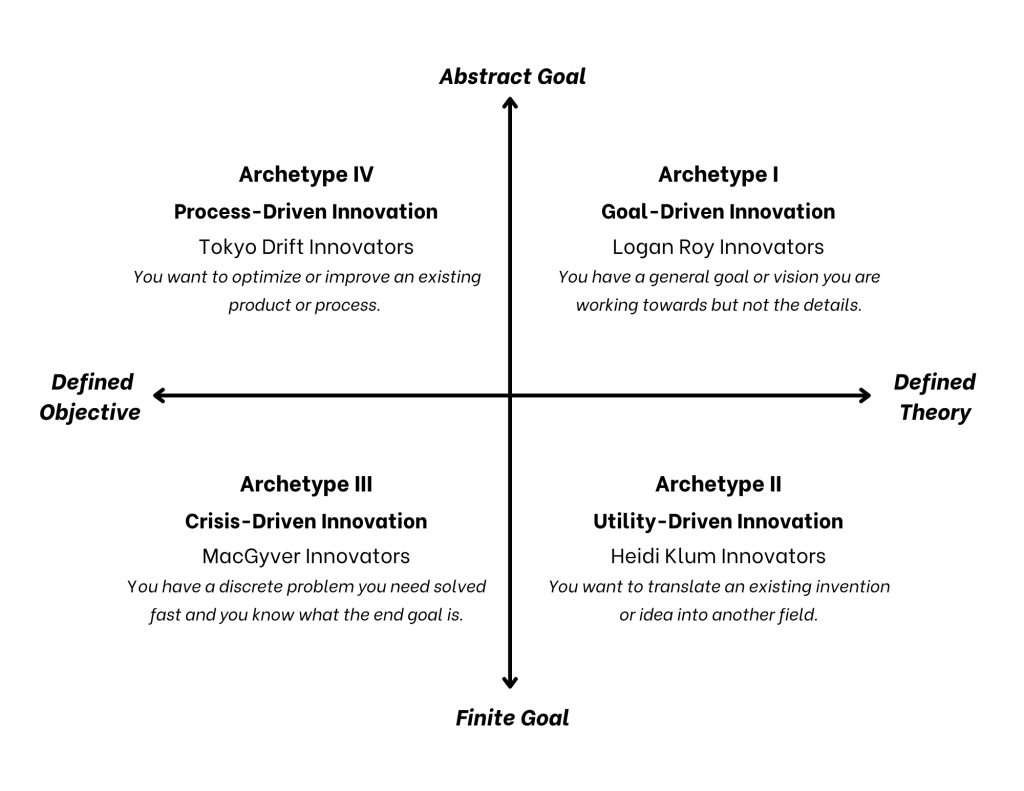

To encourage “moon shots”–creative and ambitious endeavors with the potential to be groundbreaking–calls for innovation should be as unrestrained as possible. However, different archetypes of innovation best serve different goals and problems. While the resulting innovation from each archetype can be similar, the particular circumstances and viewpoint of the innovation can change the outcome and the initial potential for success. Here, I identify four innovation “archetypes” that depend on available inputs and types of benchmarks.

The matrix describes the four innovation archetypes, nicknamed after popular TV show characters and series as shortcuts. Identifying the innovation archetype for your particular objective can define and refine the innovation process–and, secondarily, the parameters of a challenge or call for participation—address discrete problems, kickstart entire innovation ecosystems, and realize big dreams. Below, I briefly describe these in more detail.

Archetype I – Goal-Driven Innovation (“Logan Roy”)

This innovation archetype is top-down and has a general theoretical objective or goal. It could either be a general problem with many aspects, each of which needs to be solved, or a futuristic idea that is taken as an objective good. As goal-driven innovation is loosely defined, there is likely not a single solution that will result in goal achievement but numerous pieces that all have to work together.

Archetype I innovation is not usually solved by the person who creates the goal. A leader will give a directive and encourage their cabinet or council to break the goal into smaller initiatives and challenges. This is quite beneficial, as big-picture thinkers are sometimes not as clear on the details. The optimal Archetype I leader is not a micro-manager.

- Inspiration: In Succession, Logan Roy was an Archetype I innovator who surrounded himself with people he knew would fight for their own solutions.

Archetype II – Utility-Driven Innovation (“Heidi Klum”)

Archetype II innovation is focused on translating or adapting existing processes, inventions, or materials into new industries or products. This archetype of innovation can be a shortcut when there are time constraints because innovators experimentally evaluate and modify existing inventions with similar properties. Utility-driven innovation calls on innovators to use their imaginations to combine known quantities in a new way to meet a defined solution.

- Inspiration: On Project Runway, Heidi Klum tasks contestants with “unconventional challenges” to come up with “off-brand” uses for materials in their haute couture creations.

Archetype III – Crisis-Driven Innovation (“MacGyver”)

Archetype III innovation responds to a discrete, concrete problem that needs to be solved. A crisis-driven innovation should introduce new methods, ideas, or products to achieve a straightforward, single-objective defined outcome.

The most effective way to start Archetype III innovation is to work backward from the desired outcome. Often, you can search for analogs or existing mental models for similar objectives. Then, you can ascertain how to best adapt that thought process to the specific case. However, don’t let existing chemical, mechanical, technical, digital, or psychological methods impose an artificial limit that could hinder the time-sensitive nature of an Archetype III problem.

- Inspiration: MacGyver is an Archetype III innovator. On the television show MacGyver, the eponymous character often faces an urgent problem that creates a concrete obstacle with limited resources. He draws on his existing knowledge and then searches for available items he can use to build the solution. MacGyver always encounters a crisis, works backward from it, and is agnostic about the process.

Archetype IV – Process-Driven Innovation (“Tokyo Drift”)

Archetype IV is probably the most common innovation archetype, as it is focused on existing product optimization. Each part or stage of the process offers an opportunity for incremental improvement. Any decision one makes regarding any single state should never affect the overall functionality or efficiency of the entire process. If the product begins as a tire, after the innovation is complete, the resulting product can still be described as a tire. In the most optimal circumstances, nothing should change for the end user. The product’s basic objective and audience remain the same, but the operation of the newly optimized version is superior.

- Inspiration: Characters in the Fast & Furious franchise constantly tinker with their cars to drive faster or, in Tokyo Drift, to turn and “drift” with greater ease. In contrast with Archetype III innovation, where there’s a particular finite target, Archetype IV Innovation modifies an existing solution enough to exceed its proven metrics. In Archetype IV, the risk is somewhat lessened because a solution already exists; there is just room for further optimization.

Conclusion

Challenge competitions have a track record of successfully incentivizing problem solvers to bring new innovations to the market. When considering the parameters for a challenge competition, government entities, industry bodies, and NGOs should reflect on the problem at hand. This framework directs leaders to consider this archetype of innovation stimulus and find alignment among existing processes, the scale of the problem, current knowledge, the level of urgency, and the overarching goals.

For more information and detailed case studies of each archetype, click here.

Ezra Butler is a Senior Research Fellow at the Data Catalyst Institute.